Start simple. Then add complexity where it makes your life easier.

Start simple. Then add complexity where it makes your life easier.

I maintain this Hugo blog for general writing.

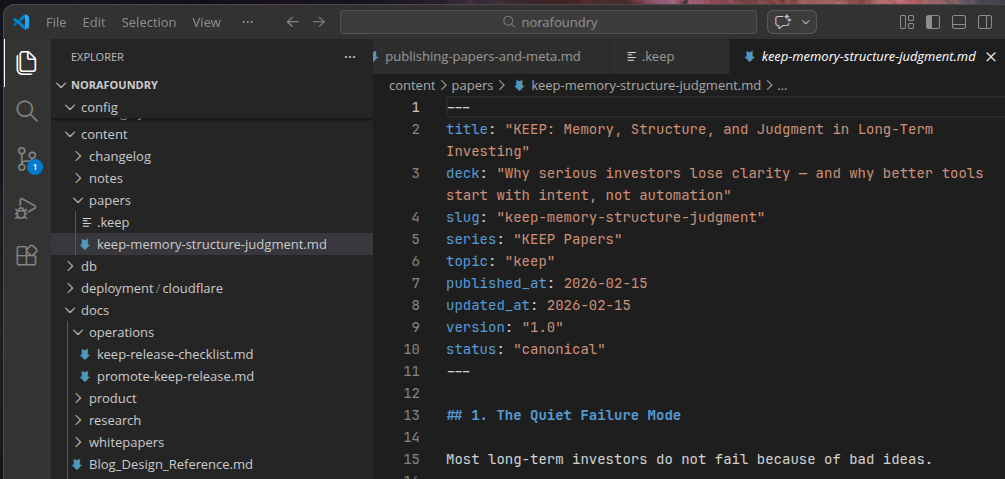

But I also needed something different inside my Rails app at NoraFoundry.dev — a way to publish position papers, technical notes, and architecture essays directly in the application.

Hugo’s great, but bolting a separate publishing stack alongside Rails for a handful of markdown documents felt like overkill.

So I built a small file-based publishing engine inside Rails.

Drop a markdown file in content/papers/. Deploy. It’s live.

/papers/keep-memory-structure-judgment

Markdown files. YAML frontmatter. No database records.

Something that did the job without friction.

Why File-Based Worked

Similar to Hugo, each paper is just:

content/papers/<slug>.md

With frontmatter:

---

title: "Your Paper Title"

deck: "Short summary"

slug: "your-paper-slug"

published_at: 2026-03-01

status: "canonical"

---

The Rails app reads files from disk, parses frontmatter, renders markdown via CommonMark, generates TOC automatically, and fragment-caches the rendered HTML.

The model loads directly from the filesystem:

# app/models/paper.rb

def load_from_file(path)

content = File.read(path)

return nil unless content.start_with?("---")

parts = content.split(/^---\s*$/, 3)

frontmatter = YAML.safe_load(parts[1], permitted_classes: [Date])

new(

title: frontmatter["title"],

slug: frontmatter["slug"],

body: parts[2].strip,

file_path: path

)

end

Figure 1: The Paper model reads markdown from disk and splits on YAML fences — no database involved.

The controller hands the body off to a Commonmarker-based renderer:

# app/controllers/papers_controller.rb

def show

@paper = Paper.find_by!(slug: params[:slug])

renderer = MarkdownRenderer.new(@paper.body)

@rendered = renderer.render # => Result(html:, toc:)

end

Figure 2: The controller passes raw markdown body to MarkdownRenderer, which returns HTML and a table of contents.

Split on --- fences, parse YAML, render with Commonmarker (Rust-based GFM), post-process headings and code highlighting with Nokogiri and Rouge. The result gets fragment-cached in the view.

No CMS. No admin. No content database.

Version control is the publishing system.

Figure 3: The entire publishing system — markdown files in a directory, managed by version control.

Starting Simple

In the beginning, I kept everything minimal.

SQLite. Solid Cache. Container-local storage.

It worked.

Fragment caching used Solid Cache backed by SQLite. The SQLite database lived inside the container filesystem.

# config/environments/production.rb

config.action_controller.perform_caching = true

config.cache_store = :solid_cache_store

That’s it. Solid Cache backed by SQLite, living inside the container filesystem by default.

Which seemed fine.

The Deploy-Time Friction

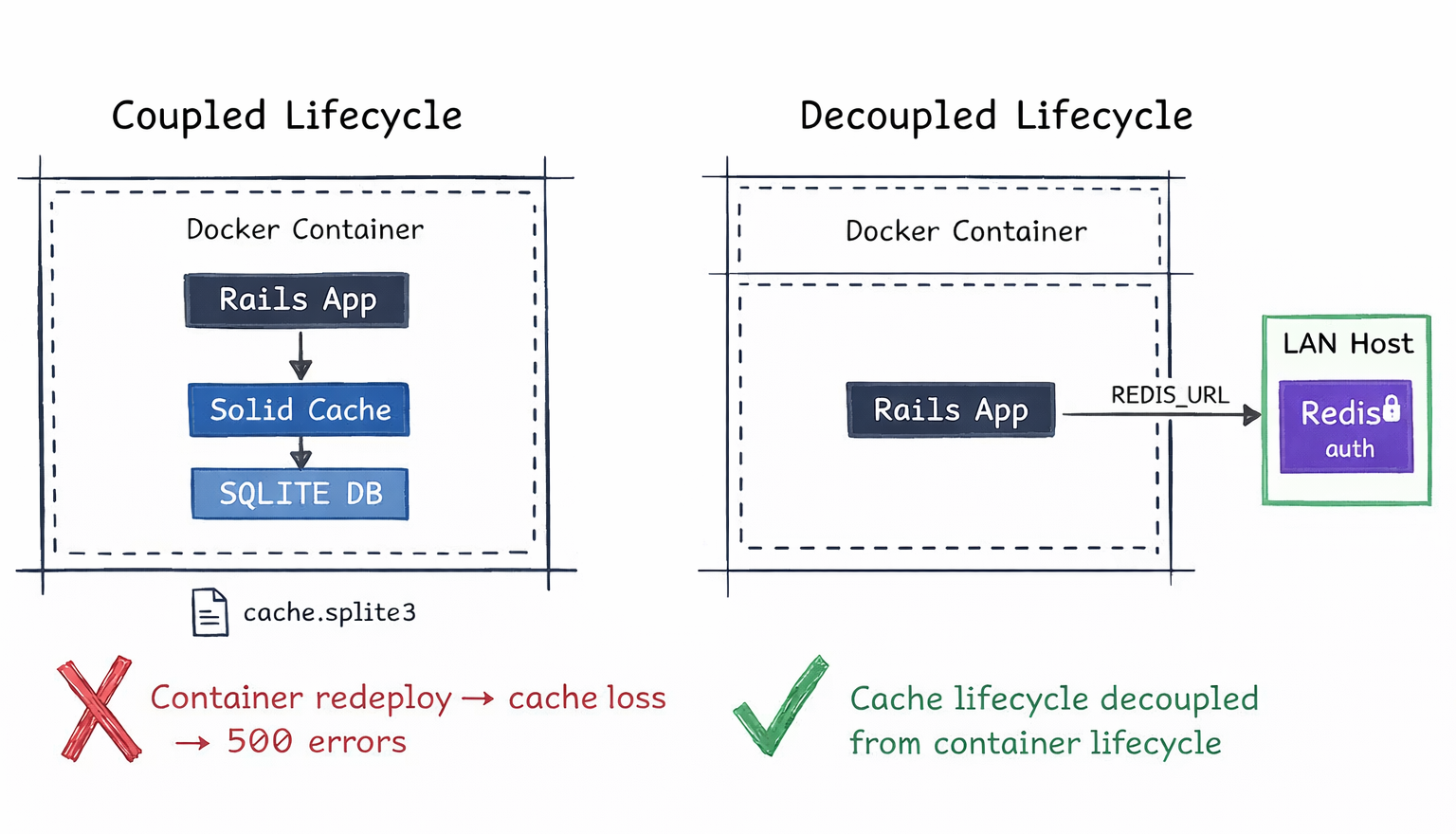

In the first pass, fragment caching lived inside the container using SQLite via Solid Cache. No extra infrastructure. No external services.

But during redeploys, the container filesystem was replaced. The solid_cache_entries table disappeared with it. The next request attempting to read a fragment triggered a 500.

Content publishing was file-based and unaffected. Caching, however, was container-bound.

That lifecycle mismatch introduced fragility. Caching shouldn’t be able to interrupt content delivery.

The Decision: Persist or Externalize

At that point, there were two reasonable options.

Mount a persistent volume — keep SQLite, but mount a host directory so the database survives redeploys.

- Minimal change, no new infrastructure

- Cache lifecycle still tied to container topology

- Harder to inspect or manage externally

- Scaling beyond one container gets awkward

Externalize cache state with Redis — move fragment caching to a dedicated instance on the LAN.

- Cache lifecycle fully independent of containers

- Centralized visibility and inspection

- Naturally supports multi-container scaling

- Adds a service and requires auth/network config

Mounting SQLite would have worked. I chose Redis because it made the separation explicit. Cache state became infrastructure-level, not container-level. And with a fail-open wrapper around Redis calls, a cache failure just means a slower page — not a broken one. SQLite errors inside the container don’t offer that same graceful path.

Not a life-or-death choice, but one that makes life easier in small ways that compound over time.

Figure 4: The core problem — SQLite cache coupled to the container lifecycle vs Redis decoupled on the LAN.

Redis in Practice

Production now uses:

config.cache_store = :redis_cache_store, {

url: ENV.fetch("REDIS_URL"),

connect_timeout: 0.5,

read_timeout: 0.5,

write_timeout: 0.5,

reconnect_attempts: 2

}

What changed:

- Deploys stopped breaking cache reads

- Fragment caching decoupled from the DB layer

- Cache state centralized outside containers

- Cache state became inspectable externally

TTL Discipline

Fragment keys look like:

paper/<slug>-<mtime>

Cached with:

<% safe_cache @paper.cache_key, expires_in: 30.days do %>

The key is generated from the file’s mtime on disk:

# app/models/paper.rb

def cache_key

mtime = file_path.present? ? File.mtime(file_path).to_i : 0

"paper/#{slug}-#{mtime}"

end

Figure 5: Cache keys derived from file mtime — editing the markdown file on disk automatically busts the cache.

Which produces keys like:

paper/keep-memory-structure-judgment-1739644800

The mtime suffix means the cache auto-busts when the markdown file is edited — no manual invalidation needed. The expires_in: 30.days TTL is there to garbage-collect stale keys. If a slug changes, the old mtime-based key would linger in Redis forever without it.

Without TTL, Redis slowly fills with dead fragments.

With TTL:

- Old keys self-expire

- Memory growth stays bounded

- No manual cleanup required

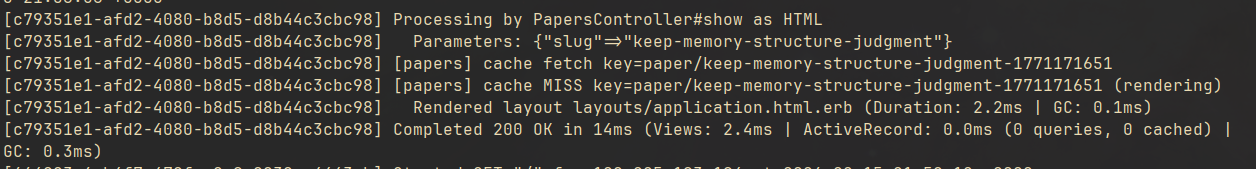

Making Cache Visible

I enabled fragment cache logging:

config.action_controller.enable_fragment_cache_logging = true

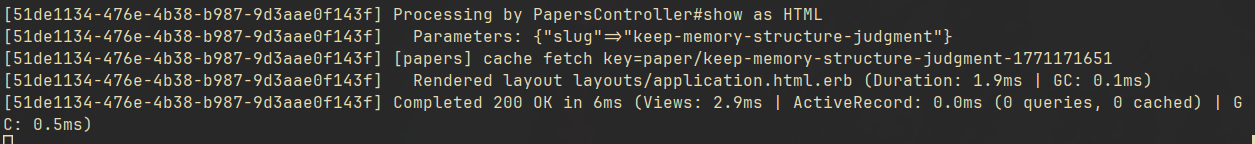

Now production logs show:

Read fragment views/papers/show:...

Write fragment views/papers/show:...

Figure 6: First request — cache miss triggers a write.

Figure 7: Subsequent request — cache hit, no rendering needed.

Cache hits, writes, expirations, and performance improvements are no longer invisible.

Fail-Open Semantics

Caching is an optimization, not a dependency.

I wrapped fragment caching in:

def safe_cache(key, **options, &block)

cache(key, **options, &block)

rescue Redis::BaseError => e

Rails.logger.warn("[cache] bypassed: #{e.class}")

yield

end

Figure 8: Fail-open wrapper — if Redis is down, the page still renders uncached.

If Redis is unavailable:

- Pages still render

- Cache is bypassed

- Users never see failure

The system degrades gracefully.

Securing Redis

Redis runs on a private LAN host, authenticated, protected-mode enabled, and injected into containers via deploy-time secrets. It is not internet-exposed. Redis is only reachable from application hosts on the private network.

# /etc/redis/redis.conf

bind 127.0.0.1 192.168.50.105 ::1

protected-mode yes

requirepass <REDACTED_STRONG_PASSWORD>

port 6379

Figure 9: Redis bound to localhost and private LAN only — not internet-exposed.

The connection string is stored as a deploy-time secret, never in clear config:

# deploy.yml

env:

secret:

- REDIS_URL

# .kamal/secrets (gitignored)

REDIS_URL=redis://:<REDACTED_PASSWORD>@192.168.50.105:6379/0

Infrastructure should default to secure.

What This Actually Was

This wasn’t really about Redis.

It was about:

- Eliminating a deploy-time failure mode

- Removing hidden coupling between cache and DB

- Introducing TTL discipline

- Adding observability

- Securing infrastructure properly

- Making caching fail-open

The publishing system stayed simple. Markdown files. Rails. Clean rendering.

But now it behaves like production software.

The Lesson

I started simple. SQLite and Solid Cache were fine at the start.

The right move wasn’t to over-engineer upfront.

It was to evolve when reality demanded it.

Start simple. Then evolve deliberately. Durable systems let you compound progress instead of chasing instability.

That’s how durable systems get built.