Why This Matters: The Shift to Agentic AI

The software landscape is shifting toward agentic AI systems - applications where Large Language Models (LLMs) don’t just answer questions, but actively use tools to solve complex problems. Instead of building separate AI features, the market and industry are moving toward AI that can directly interact with your existing systems, databases, and workflows.

This creates a fundamental challenge: how do you expose your application’s capabilities to an LLM? How do you let Claude, for instance, query your database, analyze the results or trigger your business logic - all through natural conversation?

Enter the Model Context Protocol (MCP), open-sourced by Anthropic in November 2024. MCP provides a standardized way to connect any application to Claude (or other LLMs) through well-defined tools and protocols. Think of it as a bridge that lets your applications participate in AI conversations by exposing your functionality as tools.

This post walks through building a complete MCP integration - from a local FastAPI application with PostgreSQL (a personal “goal tracking” app) to a conversational interface where you can ask Claude to query your database, analyze trends, and even update records. You’ll see the practical patterns, common gotchas in setup, and why this approach represents a fundamental shift in how we build intelligent applications.

The goal isn’t just to add AI features to your app - it’s to make your entire application conversational and intelligent by design.

The Magic of MCP: Apps Meet Conversational AI

Building conversational AI interfaces has been unlocked thanks to Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP). In this post, I’ll walk you through creating a local FastAPI application with PostgreSQL that Claude can interact with directly through structured tools - your local app talking to Claude Desktop. This demonstrates the core MCP integration patterns, and because we’re running everything locally, we won’t get bogged down with API keys, authentication, or hosting complexities.

Imagine asking Claude: “What goals do I have set up?” and having it query your PostgreSQL database, return structured data, and provide intelligent insights - all through a simple conversation. That’s a surface-level glimpse of the power of MCP.

MCP bridges the gap between your applications and Claude’s conversational abilities by providing:

- Structured tool definitions that Claude can discover and use

- Type-safe data exchange through JSON schemas

- Real-time conversations with your actual application data

Architecture Overview

The stack here demonstrates a modern Python development pattern:

Claude Desktop ↔ MCP Server ↔ FastAPI App ↔ PostgreSQL

↕

Pydantic Models (Type Safety)

Key Components:

- Pydantic Models: Define data structure and automatic validation

- SQLAlchemy: ORM for PostgreSQL with relationship management

- FastAPI: REST API with auto-generated OpenAPI docs

- MCP Server: Bridge between Claude and your application

- PostgreSQL: Robust relational database with JSON support

Project Structure

src/

├── core/

│ ├── models/ # Pydantic data models

│ ├── database/ # SQLAlchemy models and connection

│ ├── api/ # FastAPI routes and app

│ └── mcp/ # MCP server integration

│ ├── server.py # Main MCP server

│ ├── tools.py # Tool definitions for Claude

│ └── handlers.py # Tool implementation logic

Step 1: Pydantic Models for Type Safety

Pydantic models serve as the single source of truth for your data structure:

from pydantic import BaseModel, Field

from typing import List, Optional

from uuid import UUID

from datetime import datetime

class Goal(BaseModel):

"""A specific, time-bound outcome to achieve."""

id: UUID = Field(default_factory=uuid4)

title: str = Field(..., description="Clear, specific goal statement")

progress_percentage: float = Field(default=0.0, ge=0.0, le=100.0)

status: str = Field(default="active")

created_at: datetime = Field(default_factory=datetime.utcnow)

class GoalWithMetrics(Goal):

"""Goal with nested metrics for rich responses."""

metrics: List[Metric] = Field(default_factory=list)

Why this matters: These same models generate:

- Database schemas (via SQLAlchemy)

- API documentation (via FastAPI)

- MCP tool schemas (for Claude integration)

Step 2: SQLAlchemy Database Models

Map Pydantic models to database tables. This is the database layer that mirrors your Pydantic models. You’re defining the actual PostgreSQL table structure using SQLAlchemy’s ORM syntax.

The key pattern here is model mapping - your Goal Pydantic model becomes a GoalTable SQLAlchemy model with the same fields, but now with database-specific details like column types, constraints, and relationships.

The relationship("MetricTable", back_populates="goal") sets up the foreign key relationship so you can easily query goals with their associated metrics in one go.

from sqlalchemy import Column, String, Float, DateTime

from sqlalchemy.dialects.postgresql import UUID as PGUUID

class GoalTable(Base):

__tablename__ = "goals"

id = Column(PGUUID(as_uuid=True), primary_key=True, default=uuid4)

title = Column(String(200), nullable=False)

progress_percentage = Column(Float, default=0.0)

status = Column(String(20), default="active")

created_at = Column(DateTime(timezone=True), server_default=func.now())

# Relationships for complex queries

metrics = relationship("MetricTable", back_populates="goal")

Why this matters: You now have type-safe data models (Pydantic) that automatically generate both your API schemas and your database tables (SQLAlchemy), keeping everything in sync without manual duplication.

Database migrations with Alembic handle schema evolution:

# Generate migration from model changes

poetry run alembic revision --autogenerate -m "Add goals table"

# Apply migrations

poetry run alembic upgrade head

Step 3: FastAPI Routes

Create REST endpoints that return Pydantic models:

from fastapi import FastAPI, Depends

from sqlalchemy.orm import Session

app = FastAPI(title="Your Local App")

@app.get("/goals", response_model=List[GoalWithMetrics])

async def get_goals(session: Session = Depends(get_session)):

goals = session.query(GoalTable).all()

# Convert SQLAlchemy to Pydantic with nested data

return [

GoalWithMetrics.model_validate({

"id": goal.id,

"title": goal.title,

"progress_percentage": goal.progress_percentage,

"status": goal.status,

"created_at": goal.created_at,

"metrics": [metric_to_dict(m) for m in goal.metrics]

})

for goal in goals

]

Step 4: MCP Tool Definitions

Now we get to the fun part - defining tools that Claude can discover and use!

Here we are creating a “menu” of tools that tells Claude exactly what it can use from your application. Each tool definition is like a menu item that specifies:

- The name -

get_goals - What it does - “Get goals with their current progress”

- What options are available -

status_filter,include_metrics

The inputSchema is the detailed specification of those options - it tells Claude “you can filter by active, completed, or paused, and you can choose whether to include metrics (default is yes).”

When Claude sees this menu, it knows exactly how to “order” from your app: it can ask for goals, specify which status it wants, and decide whether it needs the extra metric details. This is the contract between Claude and your application - Claude knows what’s possible, and your app knows what to expect:

from mcp.types import Tool

def get_goals_tool() -> Tool:

"""Tool for Claude to get goals with progress."""

return Tool(

name="get_goals",

description="Get goals with their current progress and metrics",

inputSchema={

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"status_filter": {

"type": "string",

"enum": ["active", "completed", "paused"],

"description": "Filter goals by status"

},

"include_metrics": {

"type": "boolean",

"description": "Whether to include metric details",

"default": True

}

}

}

)

Tip: Use Pydantic.model_json_schema() to auto-generate complex schemas:

def create_goal_tool() -> Tool:

return Tool(

name="create_goal",

description="Create a new goal",

inputSchema=Goal.model_json_schema() # Automatic schema generation!

)

Step 5: MCP Server Implementation

Create the server that bridges Claude and your app.

The MCP server has two main jobs:

“Here’s what I can do” - When Claude asks “what tools are available?”, the

list_tools()function responds with a menu: “I can get goals, create goals, and update goals.”“Let me do that for you” - When Claude says “please get my goals with status=active”, the

call_tool()function:- Figures out which specific function to call (

handle_get_goals) - Passes along Claude’s parameters (

{"status": "active"}) - Runs your database code

- Sends the results back to Claude as text

- Figures out which specific function to call (

The run_mcp_server() function starts up this “translator” and keeps it running, listening for Claude’s requests through standard input/output (like a command-line program).

from mcp.server import Server

from mcp.types import TextContent

from mcp.server.stdio import stdio_server

def create_server():

server = Server("your-app-name")

@server.list_tools()

async def list_tools():

return [get_goals_tool(), create_goal_tool(), update_goal_tool()]

@server.call_tool()

async def call_tool(name: str, arguments: dict):

try:

if name == "get_goals":

result = await handle_get_goals(arguments)

elif name == "create_goal":

result = await handle_create_goal(arguments)

# ... other tools

return [TextContent(type="text", text=result)]

except Exception as e:

# Error handling - shows up in Claude logs

print(f"Error in tool {name}: {str(e)}", file=sys.stderr)

return [TextContent(type="text", text=f"Error: {str(e)}")]

return server

async def run_mcp_server():

server = create_server()

async with stdio_server() as (read_stream, write_stream):

await server.run(read_stream, write_stream,

server.create_initialization_options())

Step 6: Tool Implementation with Database Integration

Here we are creating the bridge between MCP and the database by:

- Extracting parameters from Claude’s tool call (like filtering and options)

- Querying your database using standard SQLAlchemy patterns with optional filtering

- Converting SQLAlchemy objects to plain dictionaries for JSON serialization

- Optionally loading related data (metrics) based on the

include_metricsflag - Returning structured JSON that Claude can understand and work with

Essentially, you’re translating between Claude’s conversational requests and your database’s structured data - taking natural language tool calls and turning them into database queries, then formatting the results back into something Claude can interpret and discuss with the user.

The pattern is: MCP tool call → database query → JSON response

async def handle_get_goals(arguments: dict) -> str:

status_filter = arguments.get("status_filter")

include_metrics = arguments.get("include_metrics", True)

# Use your existing database session

session = next(get_session())

try:

query = session.query(GoalTable)

if status_filter:

query = query.filter(GoalTable.status == status_filter)

goals = query.order_by(GoalTable.created_at).all()

# Convert to Pydantic for validation and serialization

goal_objects = []

for goal in goals:

goal_data = {

"id": str(goal.id),

"title": goal.title,

"progress_percentage": goal.progress_percentage,

"status": goal.status,

"metrics": []

}

if include_metrics:

metrics = session.query(MetricTable).filter(

MetricTable.goal_id == goal.id

).all()

goal_data["metrics"] = [metric_to_dict(m) for m in metrics]

goal_objects.append(goal_data)

# Return formatted JSON for Claude

return json.dumps(goal_objects, indent=2)

finally:

session.close()

Step 7: Claude Desktop Configuration

Configure Claude Desktop to connect to your MCP server:

This step instructs Claude Desktop on where to locate your MCP server. You’re adding an entry to Claude’s configuration file that specifies:

- What to call - the command to start your MCP server

- Where to run it - the working directory for your project

- How to identify it - a name Claude uses to reference this server

Once configured, Claude Desktop will automatically start your MCP server when it launches and connect to it for tool access. The result: Claude can now discover and use the tools you defined in previous steps.

File: ~/Library/Application Support/Claude/claude_desktop_config.json

{

"mcpServers": {

"your-app-name": {

"command": "/bin/bash",

"args": ["-c", "cd /path/to/your/project && poetry run python -m src.core.mcp.server"],

"cwd": "/path/to/your/project"

}

}

}

This follows the official MCP configuration pattern documented by Anthropic. Key points:

- Use absolute paths for reliability

- Ensure proper working directory with

cwd - Use bash wrapper to handle environment setup

Note: In a production environment, you’d typically have your own AI agent or application connecting to the MCP server. Here, Claude Desktop acts as our “agent” - it discovers your MCP server on startup and makes the tools available through the chat interface. This local setup enables you to quickly explore MCP integrations before integrating them into larger systems.

BONUS: CLI Integration for Easy Management

Create a CLI for managing your servers:

import typer

import uvicorn

import asyncio

app = typer.Typer()

@app.command()

def start_api():

"""Start the FastAPI server."""

uvicorn.run("src.core.api.app:app", host="127.0.0.1", port=8000, reload=True)

@app.command()

def start_mcp():

"""Start the MCP server for Claude."""

from .mcp.server import run_mcp_server

asyncio.run(run_mcp_server())

@app.command()

def migrate():

"""Run database migrations."""

subprocess.run(["alembic", "upgrade", "head"])

Usage:

poetry run your-app start-api # FastAPI server

poetry run your-app start-mcp # MCP server

poetry run your-app migrate # Database migrations

The Result: Conversational Database Interactions

Once everything is connected, you can have natural conversations with your data:

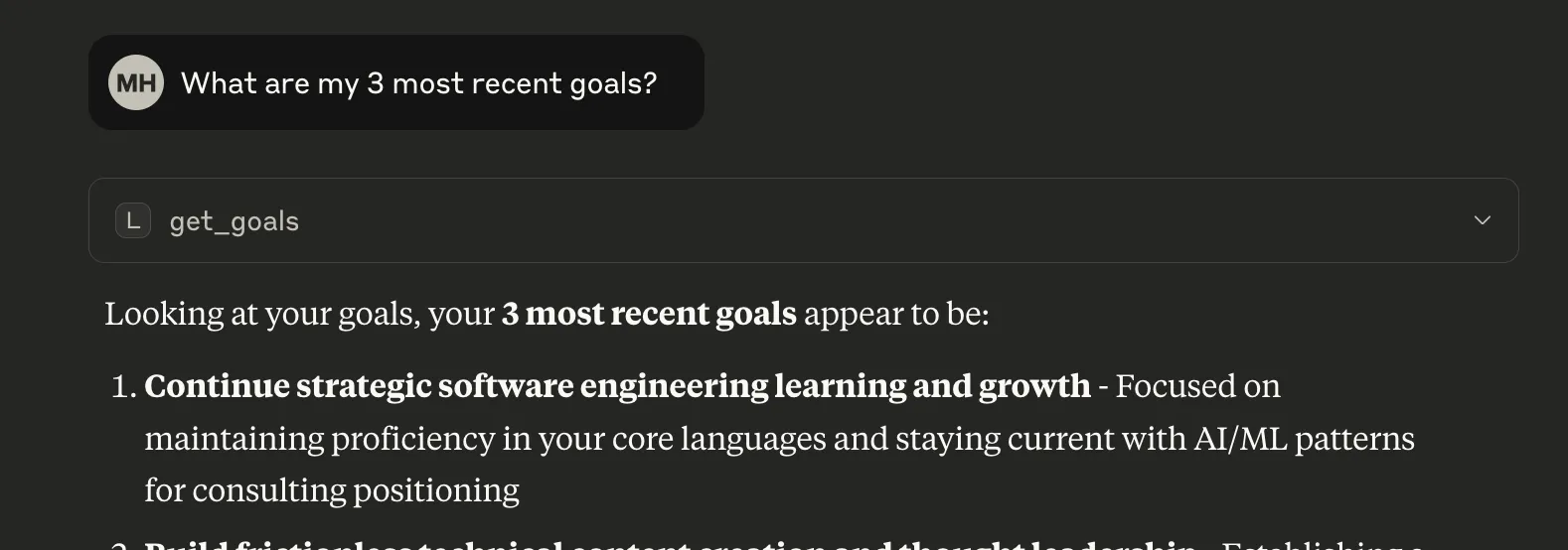

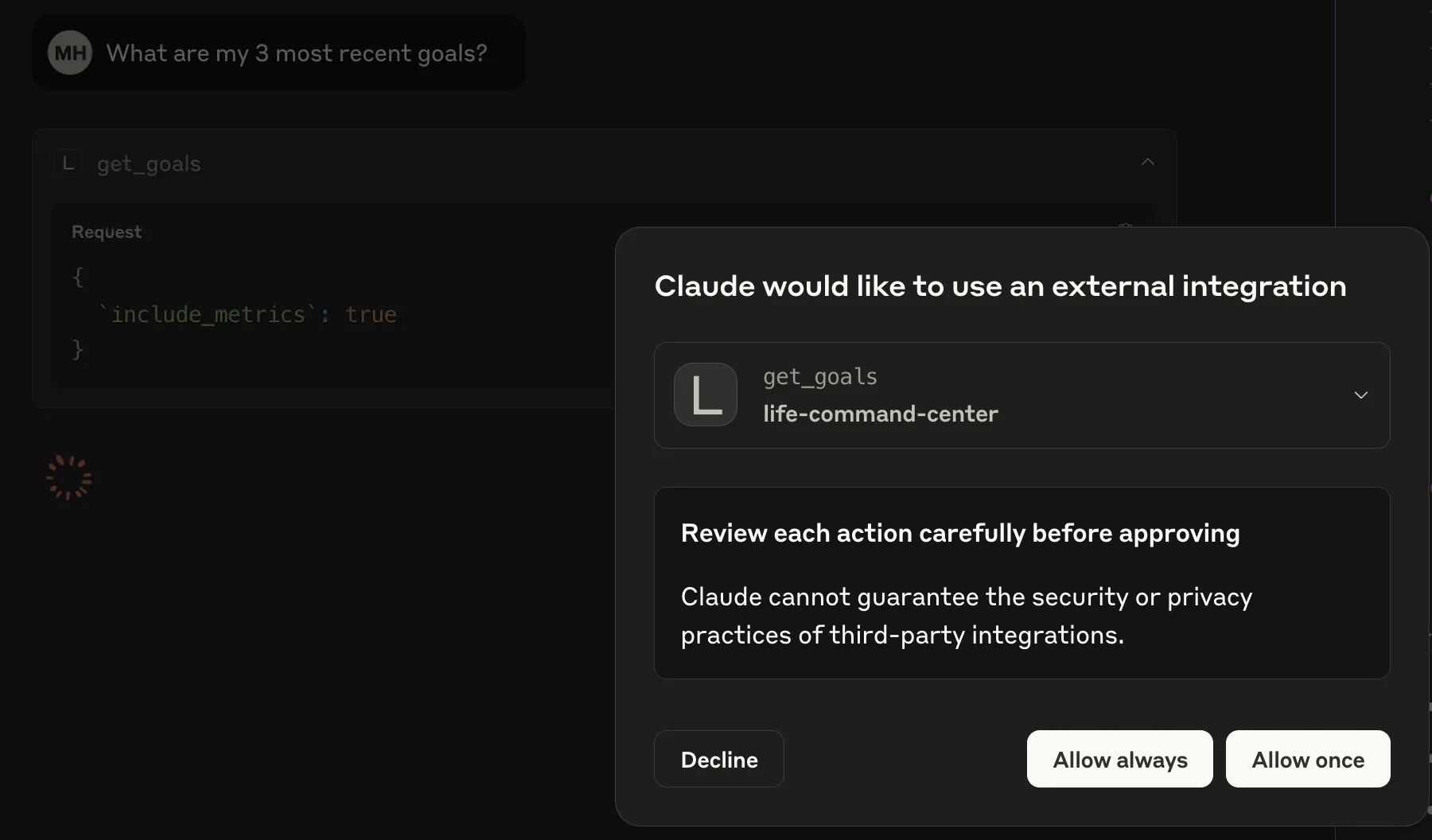

You: “What are my 3 most recent goals?”

Claude: Looking at your goals, your 3 most recent goals appear to be:

[Calls get_goals with status_filter=“active”, include_metrics=true]

Claude calls the get_goals tool and then analyzes the results to identify the 3 most recently created goals.

Claude: *Based on your current goals, I found 3 that might need attention.

You could enhance your tool definition to include:

limitparameter (number of results to return)sort_byparameter (“created_at”, “updated_at”, etc.)

That would make the call: [Calls get_goals with limit=3, sort_by=“created_at”, include_metrics=true]

Advanced Patterns

Rich Insights with Cross-Domain Analysis

Leverage Claude’s analytical capabilities:

Instead of asking Claude to run individual queries (“show me my goals”, “show me my metrics”), you’re giving it rich, interconnected data and letting it find patterns and insights you might miss.

The analytical leap:

- Raw approach: “What are my goals?” → Claude returns a list

- Rich approach: “Here’s my goals, metrics, and recent activity - what insights do you see?” → Claude identifies trends, correlations, and recommendations

Concrete example: Claude might notice: “Your deadlift goal is at 15% progress, but I see you haven’t logged any gym sessions in 3 weeks, and your recent check-ins show you’ve been deep in learning new technologies. These might be connected - your intense focus on skill development may be crowding out your strength training routine.”

Why this is powerful:

- Cross-domain thinking - Claude can spot relationships between different life areas

- Pattern recognition - Finds trends across time and different data types

- Proactive insights - Suggests what to focus on rather than just reporting status

- Strategic recommendations - Not just “what happened” but “what should I do next”

By connecting the goals app to the LLM, you’ve essentially transformed a logging and metrics app into an AI-powered personal strategist that can see the whole picture and help you make better decisions about where to focus your energy.

async def handle_progress_summary(arguments: dict) -> str:

# Gather data from multiple tables

goals = get_goals_data()

metrics = get_metrics_data()

recent_activity = get_recent_checkins()

# Return rich data for Claude to analyze

return json.dumps({

"goals": goals,

"metrics": metrics,

"recent_activity": recent_activity,

"suggested_insights": [

"Cross-reference goal progress with activity patterns",

"Identify goals that haven't been updated recently",

"Find correlation between metrics and goal completion"

]

})

Multiple MCP Servers

You can run multiple MCP servers for different domains:

Composability - you can connect multiple specialized servers to Claude simultaneously. Each server can focus on a different domain (your main app, analytics, financial data, etc.), and Claude can use tools from all of them in a single conversation.

Instead of building one monolithic MCP server, you can create focused, single-purpose servers that Claude orchestrates together. Ask Claude to “analyze my goals progress and compare it with my financial metrics” - it seamlessly pulls from multiple apps to give you cross-system insights.

{

"mcpServers": {

"main-app": {

"command": "poetry",

"args": ["run", "main-app", "start-mcp"],

"cwd": "/path/to/main/app"

},

"analytics-app": {

"command": "poetry",

"args": ["run", "analytics", "start-mcp"],

"cwd": "/path/to/analytics/app"

}

}

}

Streaming Responses for Large Data

For large datasets, consider streaming responses:

async def handle_large_query(arguments: dict) -> str:

# Process in chunks

results = []

for chunk in process_in_batches(query_data(arguments)):

results.extend(chunk)

if len(results) > 1000: # Limit response size

break

return json.dumps({

"results": results,

"truncated": len(results) >= 1000,

"total_available": get_total_count(arguments)

})

Common Issues and Solutions

1. “Poetry could not find pyproject.toml”

Error: MCP server can’t find your project files.

Solution: Configuration probably has the wrong directory. Use shell wrapper with explicit directory change:

{

"command": "/bin/bash",

"args": ["-c", "cd /full/path/to/project && poetry run your-command"]

}

2. “relation ’table_name’ does not exist”

Error: Database tables not created.

Solution: You likely forgot to run a migration - run migrations before starting MCP server:

poetry run alembic upgrade head

3. JSON Parsing Errors in Claude Logs

Error: Unexpected non-whitespace character after JSON

Cause: SQLAlchemy debug output mixing with JSON responses.

Solution: Either disable SQLAlchemy echo or ignore these warnings:

engine = create_engine(DATABASE_URL, echo=False) # Disable in production

4. Module Import Warnings

Warning: RuntimeWarning: ‘module’ found in sys.modules

Solution: This warning is harmless when running MCP servers. It occurs due to Python’s module loading order but doesn’t affect functionality.

Debugging MCP Connections

View MCP logs:

tail -f ~/Library/Logs/Claude/mcp-server-your-app-name.log

Test MCP server manually:

cd /your/project/path

poetry run python -m src.core.mcp.server

# Should wait for input without errors

Add debug output to MCP handlers:

async def handle_tool(arguments: dict) -> str:

try:

# Your logic here

result = process_data(arguments)

return json.dumps(result)

except Exception as e:

# This appears in Claude logs

print(f"Debug: Tool failed with {arguments}", file=sys.stderr)

print(f"Error: {str(e)}", file=sys.stderr)

return f"Error: {str(e)}"

Conclusion

Building MCP-enabled applications opens up imaginative possibilities for AI interactions and augmentation - transforming static applications into intelligent partners that can analyze, strategize, and evolve with your needs. The combination of Pydantic’s type safety, FastAPI’s performance, PostgreSQL’s robustness, and MCP’s conversational interface creates a powerful foundation for intelligent applications.

Key takeaways:

- Pydantic models provide type safety across your entire stack

- MCP integration is surprisingly straightforward once you understand the stdio communication pattern

- Error handling and logging are crucial for debugging MCP connections

- The development experience is smooth with proper tooling and CLI commands

- Standardized AI integration - MCP provides the protocol layer that lets any LLM interact with your applications through well-defined tools

The result is a system that enables natural conversations with your data, allows you to create complex queries through simple language, and provides intelligent insights.

Next steps: The patterns demonstrated here extend naturally to production environments with proper authentication, advanced tool chaining, and rich user interfaces. The future of AI application development leverages LLM advances to unlock the full potential of our applications, transforming them from static data repositories with APIs into dynamic, intelligent partners.

Built with: Python 3.12, FastAPI, PostgreSQL, Pydantic, SQLAlchemy, Alembic, and Anthropic’s MCP

About the Author: Mark Holton is a hands-on Software Architect at ShiftUp, where we’re building AI agents that revolutionize Go To Market and Sales Intelligence.

Originally published to Medium: https://markholton.medium.com/ai-integration-building-conversational-apps-with-mcp-f47a487009f5